The Hand That Was Dealt

“The only lies for which we are truly punished are those we tell ourselves.” (~ V.S. Naipaul, “In a Free State.”)

It’s a Sunday morning. Early. Six or six-thirty. I am seven? Maybe eight. I go down the stairs into the L-shaped courtyard that has two rooms side by side with the kitchen at the end of the row. The two rooms, I know, are rooms where Panchananda, Anil and Gunadhar sleep and have their few belongings. I’ve never seen a photo of their wives or their children. They are men who work in our household in what was then greater Calcutta. They were domestic servants. I’ve come down early to wake them up so we could play a few rounds of “29”, a card game that supposedly the Dutch introduced in India and these men taught me. I was hooked. The fact that they had worked late the night before and could use some sleep this morning didn’t tabulate with me, in my youthful obliviousness to one of South Asia’s major inequalities.

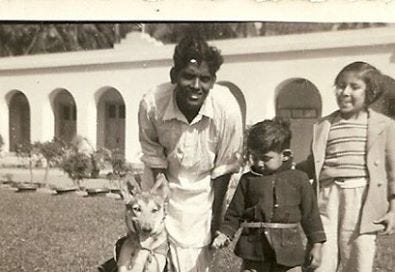

Domestic workers are in every middle-class household in India. Now, most of them live in slums or small rooms elsewhere and travel to multiple houses each day to wash dishes, cook, wash clothes, and floors. Most are women. When I was growing up, they were mostly men and they lived with us in our houses. We called them “da” as in elder brother as part of being polite, but we didn’t know their wives’ names, or their children. They went home to their villages for a month or so each year (there was no fixed vacation) and sometimes didn’t return for a few months, feigning illness or a death in the family. At times, these stories became the butt of jokes. Panchananda, who had been with my father ever since 1942 when he was picked up one wintry night from a gas station somewhere between Krishnagar and Calcutta during the Bengal Famine, couldn’t keep straight how many times his wife had died to eke out a few extra months of home visits.

In a child’s reality, their lives were gauzily different. We said they were part of our family, and we didn’t mistreat them. But neither did we think of them as our equals, dreaming dreams, hoping for a better future for themselves and their children.

Today, all my friends and acquaintances in India have domestic help and no one that I know mistreats them and many, in fact, treat them with respect and caring. One of my adopted nieces (my best friend’s niece) thanked the domestic workers in her Kolkata household in her Ph.D. dissertation. Perhaps a new India is possible.

However, there’s a vast world of unremitting harshness and domestic workers are swept along in a tidal wave. The informal sector, unorganized sector, of the economy in India is as high as 83 percent of the workforce. Measurement is sometimes difficult. Ration cards and IDs are one way but that is not always the case. Over 90 percent of the informal sector have no written contract, no paid leave, no benefits. It is said that half the Indian GDP is from the informal sector.

In 2008, Aravind Adiga won the Man Booker Prize for a debut novel, The White Tiger. The main character is a driver, a chauffeur, from rural India, working for an upper middle-class family. The narrative is from the point-of-view of the chauffeur. In the novel and in the subsequent film that was made of it, the chauffeur, having given his service and respect to his employers, is betrayed by them, and falsely accused of a grievous crime. He kills one of his employers in anger that is as complex and deep as the subcontinent’s social armature. I am not here to argue the literary merits of the novel. Adiga wrote in the white heat of modern India, asking those who are employers some basic questions about equity. His critics are many. Who wants to see proverbial cockroaches scampering across marble-tiled floors of airconditioned apartments in the glittering suburbs?

I quote from a few sentences:

“These people were building homes for the rich, but they lived in tents covered with blue tarpaulin sheets.”

"A handful of men in this country have trained the remaining 99.9% - as strong, as talented, as intelligent in every way - to exist in perpetual servitude."

And . . . this knife thrust that all South Asians reading this piece will recognize:

“I saw him take out a thousand-rupee note, put it back, then take out a five-hundred, then put it back, and take out a hundred. Which he handed me.”

So where are we with about 4 million people who work as domestic workers in India?

My friend, Gargi Sen, who I met through mutual acquaintances on social media and with whom I chat on WhatsApp, sent me her documentary Home/Work, 42.36 minutes and made in 2012 about a group of women who work in Rajasthan and Delhi as domestic workers. Their stories are familiar nationwide. I will leave you to imagine what their lives were like during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Gargi is well-known in India among independent documentary and short-film makers through her cofounding of Magic Lantern Foundation, which distributed their work till recently.

I hope you’ll watch Home/Work (it’s subtitled) and leave comments below.

“Do we loathe our masters behind a facade of love – or do we love them behind a facade of loathing?” (from “The White Tiger,” Aravind Adiga)