To Look without Fear

“Life breaks everyone.” (~Ernest Hemingway, A Farewell to Arms)

The researcher was explaining the ground rules of what seemed like a very easy exercise. I was to view a video for about a minute and then answer a series of questions. Easy-peasy.

The video furrowed into focus. Sets of young people, students, entered and exited from either end of the frame, carrying books, back packs, high fiving once in a while. The movements seemed like they were on a loop. Repetitious. I tried to look for patterns and pairings. The video ended.

After a quick few questions of did I see X and Y, which I answered correctly, the researcher asked, “Did you notice the theft of the backpack?” What??? There was a theft? Which corner of the frame? I had no clue. It was as if I had watched a different video from the researcher. She continued, “Did you see how the backpack was handled between the accomplice and the thief?” I GIVE UP!

If I couldn’t notice what was in front of me a minute ago, I wondered about my memories of decades ago. What did I remember? Well, “truth” would be a word carved into stone at the bottom of the pedestal of a statue of someone sitting on a horse looking like he knew where he was heading. I don’t know about THE TRUTH. I know of only mine. Mary Karr, the prom queen of memoirists had written: “I once heard Don DeLillo quip that a fiction writer starts with meaning and then manufactures events to represent it; a memoirist starts with events, then derives meaning from them.” (The Art of Memoir, 2015, p. xvii).

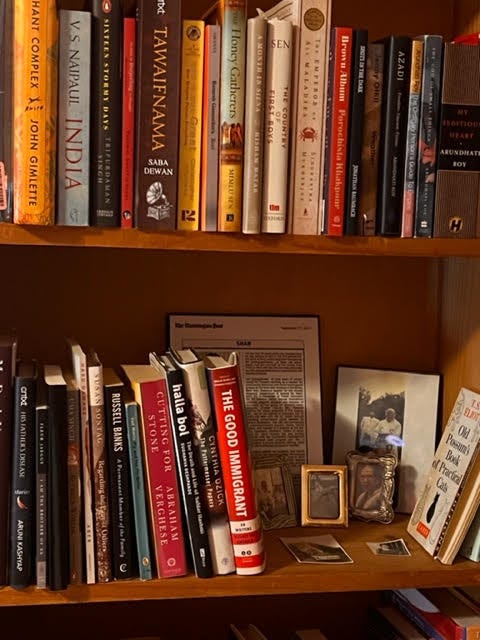

The padlock weighs at least three pounds, possibly more, solid metal. It can maim or kill a living creature if thrown with some force at a decisive angle. The key is long lost. The memory of where the padlock was used is also lost. I do remember my mother walking around the house with a jangling set of keys tied to the aanchal, the free drape of her saree over her shoulders. The house whose doors the padlock secured is also gone. I keep the padlock on a bookshelf in my apartment, over 7,700 miles from where it served its serviceable purpose.

Why save an instance of memory? Of the millions and millions of memories that make a lifetime for most of us, why do we invoke and the beseech some fragments? As in the psychology exercise that I mentioned above, much is forgotten and overlooked and in remembering some, almost unconnected, fragment unbolts a life that will surely vanish after I am dead.

Memory for ordinary people like myself, as contrary to the famous and the notorious, has a life span of a generation or two. My sons and their children probably won’t be able to or even choose to revivify my meager holdings of memory. This fact, the loss of memories within a few generations, is new to me. It never occurred to me when my parents were alive forty years ago. Now, I wish, I had the repository of tales within my reach. Saul Bellow, in a letter to Martin Amis, wrote that “losing a parent is something like driving through a plate-glass window. You didn’t know it was there until it shattered, and then for years to come you’re picking up the pieces — down to the last glassy splinter.”

I tilt toward memories to reconsider, reappraise my life long past. I don’t speak for others. Many who have suffered trauma and have no desire to revisit the dank darkness. The minor trauma that I experienced has taught me a bit, though decades later, of who I became. As a young boy, who felt helpless against a formidable parent, I remember shadowboxing in front my bathroom mirror. I saw a fictional character in a movie recently, doing exactly that and for the same reason. I didn’t know it then. I do now. I’m not that special. There’s comfort in that. I belong to that cauldron of memories.

And all are not happy memories. The bone-crushing disappointments; the hypnotic anger; the comfortless sorrows. My friends provided me with some: Alaskan huskies licking a small girl’s spectacles because she was just at that height; a prepubescent girl writing well-crafted sentences to her parents pleading her case to be taken home from summer camp; a young girl on a Mediterranean island realizing that the death of a classmate’s father was due to political terrorism. A young boy who snipped his stepmother’s long hair while she slept. My mother and I arguing over the cuff width of my trousers—eleven inches or twelve (this was in 1964)?

In a world that captures so many memories effortlessly through photographs, digital media, and audio files, why bother to harpoon moments idling in the deepest recesses of my mind? To remember, to affirm and accept is to live without fear, to countenance my life in all its fullness.

_____________________________________________________________________

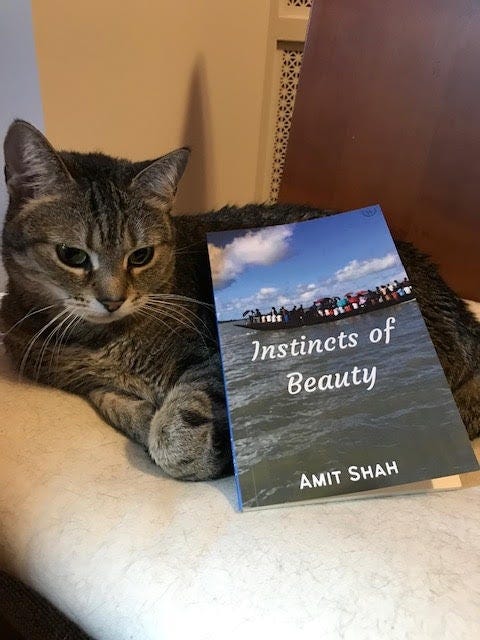

Forthcoming in 2023

I have signed a three-book contract with a small commercial publishing house in India, Red Lantern Books. The first book in 2023 is a memoir-biography of my great-grandfather: In the Shadows: The Life of Lal Behari Shah and the Calcutta Blind School

congratulations, Amit!

Congratulations on the book deal!