In 1984-1985, in New York City, I was 34 years old and working as a production editor with St. Martin's Press. Long before computers, I had a Selectric typewriter and a telephone for what constituted the sum total of "communication channels." I chain-smoked Marlboros and drank gallons of coffee. In the evenings, I lived with my then-wife in a railroad apartment on the fringes of what is now an exclusive neighborhood in Park Slope, Brooklyn, a refugee from Manhattan. I drank Scotch on the rocks and thought of how to harness the energy of many of my colleagues in a literary venture.

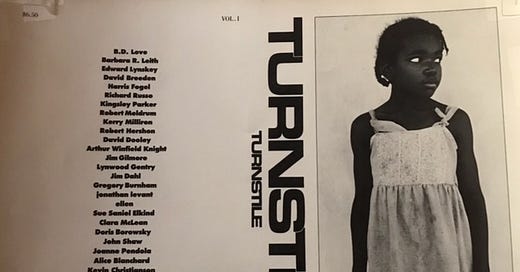

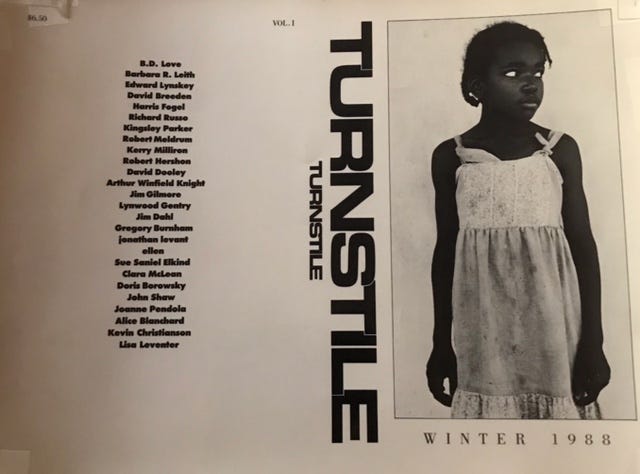

I put out a broadsheet typed, and retyped, a million times by someone who is today the editorial head of one of the world's foremost publishing houses. I sent that broadsheet that contained a plea for dollars to start a literary magazine that would include short fiction, photography, poems, illustrations, and nonfiction as often as we could bring it out. I also asked for volunteers to help staff the effort.

By the end of that day, we had raised about $600 just from St. Martin's Press. Later, I hit up everyone, I mean everyone I knew. People gave money because they knew me and my colleagues. But did they already know it was unsustainable? Perhaps. But good dreams are food for our souls. And we went to work.

Lindsey Crittenden's piece below (#1) is about that birth.

1. https://lindseycrittenden.com/what-i-did-for-love/

In 1989, in February, the fatwa against Salman Rushdie was announced. The writer went into hiding (read Joseph Anton for Rushdie's recounting) and furious debates took place in publishing halls about whether Rushdie should be published at all to safeguard others. The debate did take place in our tiny group in lower Manhattan. We published an issue where we had my dearest friend Una (who had met with Rushdie a few years before) publish an edited interview as well as an essay she'd written about fiction by non-English writers writing in English. (#2 and #3)

2. http://www.subir.com/salman-rushdie/una-chaudhuri-imaginative-maps-rushdie-interview/

3. http://www.subir.com/salman-rushdie/una-chaudhuri-writing-the-raj-away/

Our issue also contained an editorial/publisher's note on first amendment responsibilities and support for Rushdie.

I mailed a copy with a brief note to Rushdie, care of his literary agent of the time, Andrew Wylie, in New York.

Sometime a month or so later, I was in my office, overlooking Central Park, of a travel publisher that I worked for, then at Columbus Circle, which is now a Trump hotel. The phone rang. It was on my right. Caller ID hadn't been invented. We were in the FAX age as well.

The man on the line, with his unmistakable well-bred English accent that had become so familiar to us from TV reports, said that he wanted to thank us for the issue.He remembered my friend Una from when writing wasn't a blood sport. I was sooooooooo excited. Almost scared. I couldn't breathe a word about this. I had no proof. It was the greatest gift and it was only for me? I did tell two people.

Later that year, suddenly Rushdie appeared at Columbia University seemingly out of nowhere and then disappeared into the night. Ayatollah be damned!

In those days, I would read a writer and if I liked him/her call them up and ask if they had anything they could give for us to publish for free! This among some writers who were starting out. Of the now-famous, the ones I called and got pieces from were Lawrence Wright, Richard Russo, Jane Smiley, William Kennedy, Pam Houston, T. Coraghessan Boyle, Paul Auster, Geoffrey Ward.

Would I take on such a Sisyphean task of publishing a literary magazine without money or distribution today? No, I wouldn't. My day is done.

I'm so glad and grateful for that self that found courage and solace from words by writers such as the ones below.

With gratitude,

Amit

----------------------------

(From Gabriel Garcia Marquez's Nobel speech)

"On a day like today, my master William Faulkner said, ‘I decline to accept the end of man. I would fall unworthy of standing in this place that was his, if I were not fully aware that the colossal tragedy he refused to recognize thirty-two years ago is now, for the first time since the beginning of humanity, nothing more than a simple scientific possibility. Faced with this awesome reality that must have seemed a mere utopia through all of human time, we, the inventors of tales, who will believe anything, feel entitled to believe that it is not yet too late to engage in the creation of the opposite utopia. A new and sweeping utopia of life, where no one will be able to decide for others how they die, where love will prove true and happiness be possible, and where the races condemned to one hundred years of solitude will have, at last and forever, a second opportunity on earth. "

_________

(Salman Rushdie)

https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v04/n18/salman-rushdie/imaginary-homelands

(Amitav Ghosh)

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/oct/28/amitav-ghosh-where-is-the-fiction-about-climate-change-

(Arundhati Roy)

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/jun/17/arundhati-roy-interview-you-ask-the-questions-the-point-of-the-writer-is-to-be-unpopular