“Whatever happens. Whatever

what is is is what

I want. Only that. But that.”

(“Prayer” by Galway Kinnell)

(Writer’s Note: A portion of this essay was previously published under the title “Hour of Our Death”)

***********************************************************************************************

There was no farewell. No goodbyes at the edge of the tarmac. No fading arms waving as the train pulled out of the station with engine smoke mushrooming the platform, of course in black and white.

Instead, it was a bored-sounding telephone operator reading a transatlantic telegram over the landline at midday.

It’s been 38 years since my father died. He was 66. I was 33 .

He and I are tethered. Not oppressively anymore though that was the case for decades. Or is it what I tell myself to lobotomize the unspeakable?

He was a gifted man. Gifted in his determination to get things done. Gifted in the things he did get done. Gifted in connecting with people and making them feel at ease. Gifted at wading into a crowd and making himself at home. Gifted in sucking the oxygen out of the room and leaving me gasping for breath.

He was a stupendously difficult and flawed man. My mouth runs dry at the ways he fell short.

And yet, I’ve become the chronicler of his memory, polishing, dusting, making the sharp corners shine. Why? Why, am I the chronicler? Because I am the loyal son? Or is it that the incandescence of his public life cast my shadow longer, larger, more muscular?

Once that incandescence was like a searchlight with dogs barking. Now simply a light on a life that nurtured me.

I came to the United States because of him. He was a young Bengali man, barely 22, in the fall of 1939, a month after the declaration of the Second World War, who boarded the United States Lines passenger liner President Harding in Southampton, England, for New York harbor. Americans fleeing Europe had overloaded this vessel with almost 597 passengers, and non-Americans such as my father had to get special authorization from the US Ambassador to the Court of St. James, a man named Joseph Kennedy, the father of the late president. But that’s in the future.

My father had a scholarship to start a certification program for teaching the visually handicapped in the fall of 1939 at Teachers College at Columbia University, and he was already delayed as his ship from India, SS Mooltan, brought him only up to Marseilles in August 1939. He crossed France and into London by train just days before the formal declaration of war on September 1, when he was issued a gas mask and started helping volunteers sandbag air-raid shelters. As a former Boy Scout — he had started the first Scout troop for the blind in Asia — he was relieved to be occupied and of service.

In the many tellings of that dramatic voyage, my father insisted (as is standard feature of dramatic scripts) that as he walked up the gangplank of the ship at Southampton, a man, perhaps insane, shouted at him, “You, Hindoo, don’t go! You will drown!” I have no way of verifying that such a statement foreshadowing the events did occur. The story was added flavor for a bug-eyed 8-year-old, though.

The overloaded President Harding sailed into the North Atlantic, weighted by its passengers fleeing from a continent about to erupt into flames. German U-boats swarmed the Atlantic waters, and my father had a front-row seat to the cat-and-mouse maneuvers of French tankers like the Emile Miguet and British freighters like the Heronspool, which were both torpedoed. The Harding ended up rescuing crews from these vessels.

Around 9:30 p.m. on the night of October 17, 1939, 300 miles south of St. John’s, Newfoundland, and 1,000 miles from New York, the strongest Atlantic storm up to that time hit — and it hit the US Lines’ President Harding with category 4 hurricane winds of 130 to 140 mph, tilting the liner to angles that caused injuries and deaths. Furniture and pianos went crashing into human flesh, breaking bones. One such victim was my father, who broke his left leg in three places. Once again, having been a Scout, he managed to help with splints and bandages assisting the ship’s surgeon, Dr. Thomas Fister (how do I know that name? I researched the microfilm collection of the New York Times at the Brooklyn Library a few decades ago).

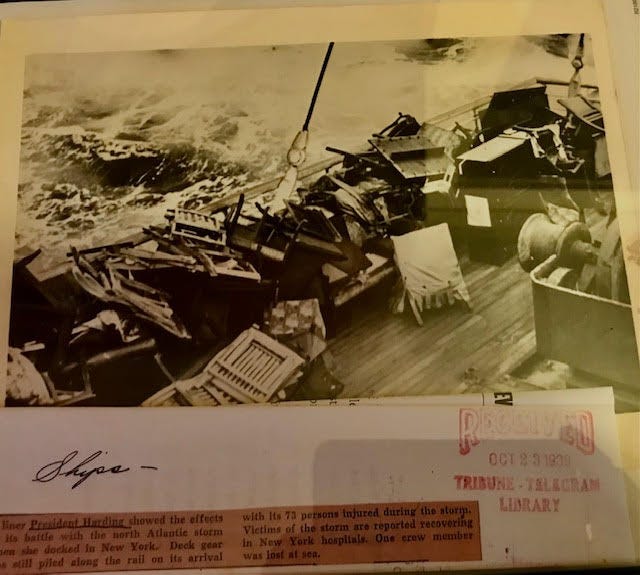

On October 18, the US Coast Guard cutter Hamilton, off Boston, got the call for medical supplies. It responded and escorted the damaged liner to New York, on October 21st to the West 18th Street pier, completing the 11-day odyssey. “With flag at half mast, afterdeck piled high with splintered furniture, and saloons and staterooms half wrecked, and with three uninjured members of the ship’s band rendering a poignant “East Side, West Side,” the United States liner President Harding docked here early yesterday …” reported the New York Times.

He only had a high school education and hard-knuckle life experiences when he reached these shores with a broken leg, very little money, and a ton of hope. This country, he always said to me, accepted him for what he was — an intelligent, quick-witted, enormously inventive young man who wanted a chance. That’s the way he always saw it. Americans were can-do people without absurd limitations. They rolled up their sleeves at Thanksgiving dinner, he’d tell me, at a time when starched collars were di rigueur in the Indian heat. He didn’t tell me about Jim Crow and what he witnessed in segregated school campuses for the blind south of the Mason-Dixon. Nor did he elaborate how his friends in New York would always rush into fancy midtown restaurants before him to let the maître d know that the brown-skinned man was Indian (the turbaned sort) and not a light-skinned American Black.

One of his professors, the founder of the Teachers College program, the late Dr. M. E. Frampton, obtained a lawyer for my father, who participated in a class-action suit for damages against the United States Lines. This money was paid out.

The poor Bengali scholarship student, who was also a car enthusiast (he had 26 cars in his lifetime), bought his first car in the United States with the financial compensation and started touring schools for the blind across the country. He discovered that once he crossed a certain geographic point on the Mid-Atlantic Coast, physical segregation of the races was the rule of Jim Crow. But that’s another story and he never spoke about it very clearly. What he did speak about was how a colonial British-Indian passport holder escaped the class and societal strictures of orthodox and colonial India and the stifling stratification of England, to find a home in the land of opportunity for most. And that land became the beacon when I looked for a familiar shore. In the world I inhabit today, that’s a pretty naïve gaze at an America riven with racism. Was he aware of the darker side? Of course he was but true to his nature, he told the story he wanted to tell. In that he became the quintessential “self-made American.”

His grandfather, Lal Behari Shah, had started the first school for the blind in eastern India in 1894. A printer by trade, he has started to lose his eyesight in his forties. Christian missionaries taught him English Braille. He created a version of Bengali Braille, which was known as Shah Braille. It was in use till the 1960s. The school, which my father headed from 1948, when he was 31, is still in existence. When you build something out of nothing; actually it was out of banana groves that were cleared for a library for Braille books and, later, for training for computerized production of multilanguage Braille materials, and have it forever incised on a national postage stamp, you can claim your public life a marvel.

The government gave him a medal. The fourth-highest for public service. It was 1961. He was 44. I was 11. Jan. 26. I knew the night of the 25th when a reporter called to tell him. I was next to him as he tied a starched dhoti on me, as we got ready for some wedding dinner or some such. He cried. It was only 14 years after independence. This then was a big deal. There were 26 recipients that year. There are 102 today.

What I internalized over a half century and more ago was of my doing. The struggle of the ego and self-esteem. He did what he could. Much more than I had any right to expect. I chased him up the hill, but I knew long ago that I’d never catch him. Not that he was running away from me. This was who he was. Gifted, maddening. Loathsome and loving.

And the private and clandestine life? The one that all of us live? The secrets, the sorrows, the pain, the shame? If I weren’t his son, I’d go to town as the chronicler. But mercy is what I seek too. A place to rest my head next to his. Once more.

His effect on his children, his wife, and his closest in-laws was at times cyclonic and dark as the darkest night.

And then would come the dawn . . . and he’d get Didi and me up and say, “Let’s go and have breakfast in the national park.” And off we’d go as the sun would glint and shimmer, shoving the night’s dullness onto the wayside.

It took a lifetime to sort all that out and it still is a journey. No longer a dusty road but a path in the woods with surprising clearings along the way.

I often think: What would he have done? And tell myself, Don’t do that! But more often, I think: Do exactly that — be brave, be bold, be loving, give more than you receive, talk to people.

And more often, I think: Do what he couldn’t do ---ask for forgiveness.

From Jeff Ikler: Beautifully written, Amit. Lyrical. Your father sounds enormously complex and reminds me of my own. What of him have you become? What of him have you set down by the side of the road and walked on?

Love this piece! And the title is so perfect! Keep writing!