Darkness is a Shade of Light

"Talent is insignificant. I know a lot of talented ruins. Beyond talent lie all the usual words: discipline, love, luck, but, most of all, endurance." (~James Baldwin)

An acquaintance from Bengal recently asked me, “Where’s your father’s family from?” To the uninitiated, in India EVERYTHING is connected to one’s village, caste, and community. Even generations later, people can rattle off where their ancestors were from. I faked it a bit. “North Bengal”, I said vaguely, “Murshidabad and Krishnagar.” The knotty journey from the Punjab in the West to Gangetic plains of north Bengal is still a mystery to me. My mother’s side had a clear-cut trajectory. Progressive, landed gentry from Bardhaman (anglicized Burdwan), they were central to the Bengali Renaissance of the mid-19th century, living in joint-family courtyard-ringed houses in north Calcutta, Rambagan.

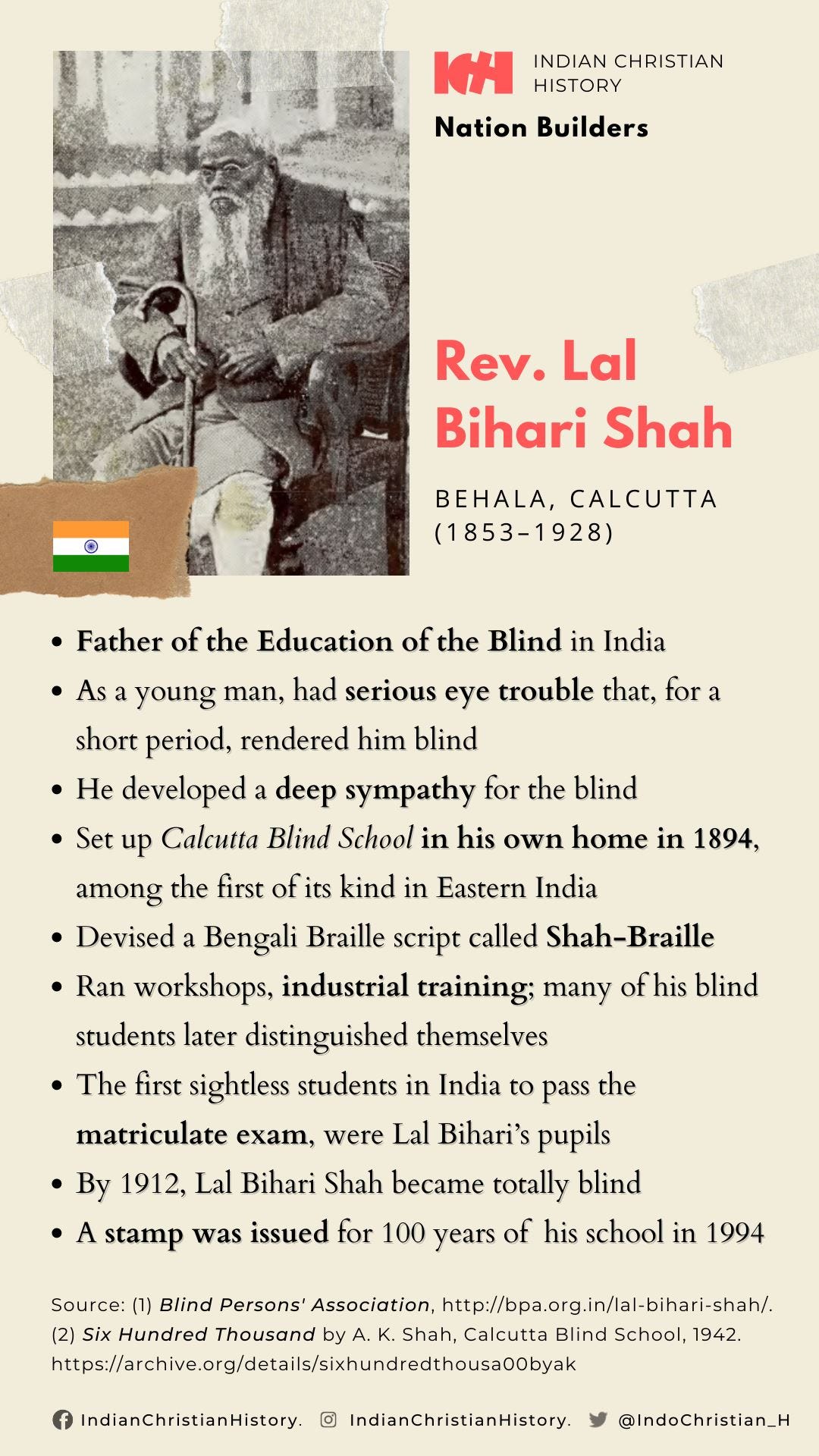

My father’s side of the family has had the most direct thump on my life. And all because of Lal Behari Shah, who started it all. In short, he started a school for the visually impaired in eastern India. It was the first started by an Indian. The others had been missionaries. He developed (and here there’s some murkiness) a systematic Braille script for Bengali (though the first iteration was someone else’s. What was the fine-tuning? I have no idea. What I do know is that the Bengali Braille script was called Shah-Braille and lasted till the 1960s. In 1943, a commission was convened to create an Uniform Braille Code for Indian languages, which became Bharati Braille. My grandfather, Arun, one of Lal Behari’s sons, was a member.

Lal Behari Shah was my great-grandfather from my father’s side. He died in 1928 so I never saw him. Yet my whole life not only wreathes around him, but it borders my entire life.

The house I grew up in, on one corner of the campus of a school for the visually impaired, started by him in 1894 at 154 Kareya Road in South Calcutta (now Kolkata), later moved to 194 Lower Circular Road, and finally to the suburbs in 1925. The land was donated by the government of Bengal at the urging of the then-governor of Bengal, Lord Ronaldshay. The main school building was inaugurated by Lord Lytton, who became the Viceroy of India, on the 31st of March, 1925. I knew almost every corner of that building as a child running around that campus and rough-housing with children my age.

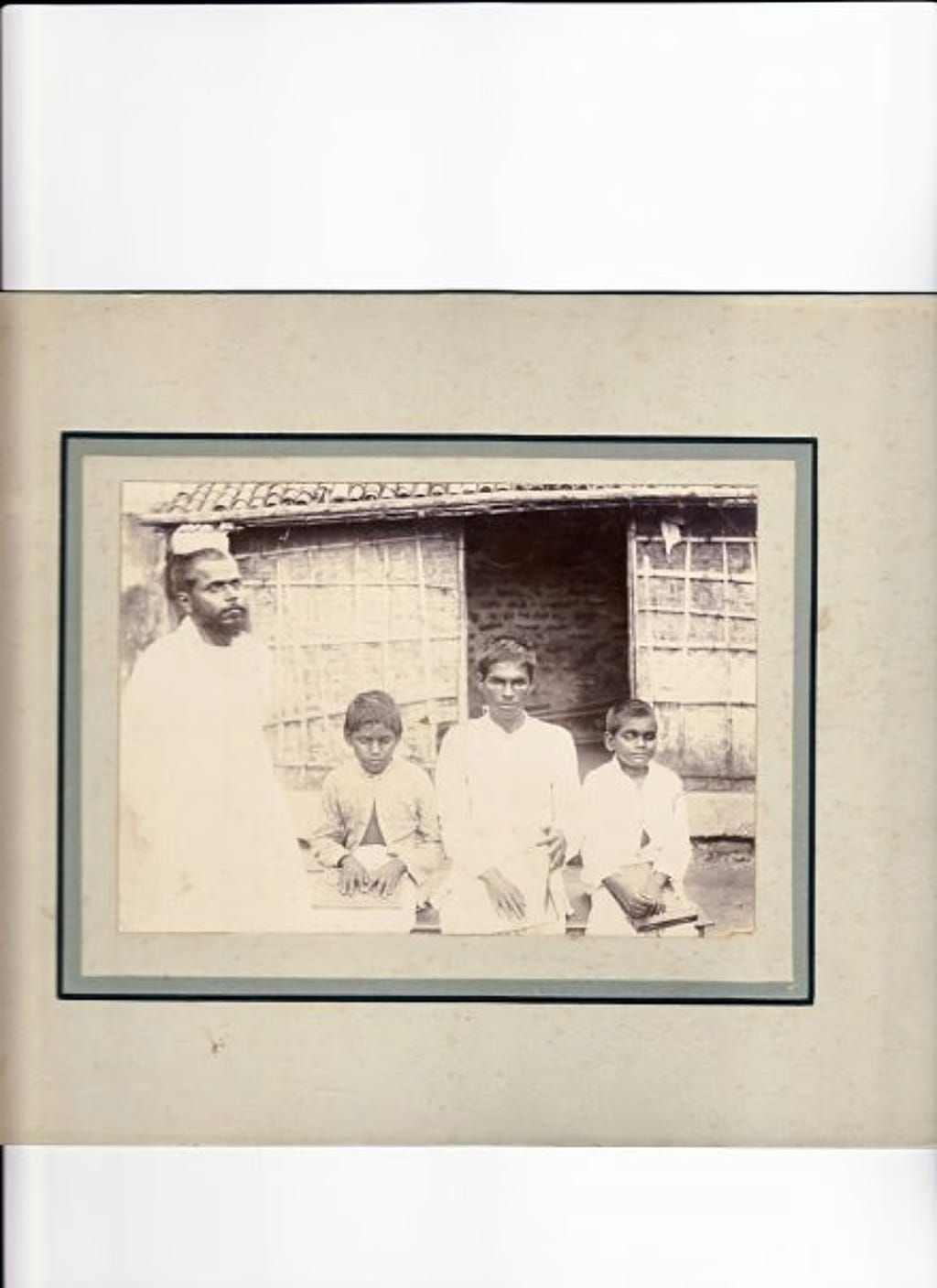

(Lal Behari Shah with his first students. Courtesy the author. All Rights Reserved)

Writing a biographical account of Lal Behari Shah, doubtless an original in education in India, is a minefield of historical befuddlement and craters. Over the years, I’ve shadowed a number of privately published versions of his life, even an account from a researcher from Russia, who wrote me years ago. Online, translated from the Russian, is this extract that I cannot verify but am intrigued and amazed, especially about the books in the library.

“On February 16, 1918, Yeroshenko wrote to Toria again: “ I am still in Calcutta. I have stopped at the house of a blind Indian, a teacher at the local school for the blind. This Indian has a large library of Braille books (in English). I spend all day long reading and studying, and in the evening I go to lectures. I have several friends who read books on theosophy and other books. I literally live a student life.” He emphasized more than once that he would like to get to know the Indians. It becomes clear why it was important for Yeroshenko to live among the “natives.”

It is clear that Vasyl is still looking for work, but the political situation is changing rapidly, and the Russian subject is becoming increasingly inconvenient for everyone after the October Revolution in Russia: both for his American patron Agnes Alexander and for the British authorities in India. It seems that in British India from November 1917 to mid-1919, Yeroshenko was left to himself by everyone. However, it was at this time that the blind young man, who three or four years earlier recalled how he was afraid of and did not understand sighted people, finally learned to survive successfully on his own. Vasyl Yeroshenko used a rich English-language Braille library that had been collected in the family of Lal Bihari Shah and his son Arun Kumar Shah.”

The material, at first glance, seems like a gold-mine for a biography but the dead-ends are at every corner. Even house numbers from the mid-19th century Calcutta don’t match from account to account. The hagiography is overwhelming. Sometimes, even laughable as parables and mythologies about Lal Behari’s own great-grandfather, Budhui Shah (Sayyad Muhammad Badaruddin Shah) abound. In all the sources I have, the late 18th and the early 19th century is the farthest I can track this lineage.

The questions I have and want to explore are:

· Why did Budhui Shah become a mendicant and hermit?

· How did he become acquainted with William Carey, the celebrated Indologist, at Serampore. Carey was a missionary, founded the first degree-granting college in India, and converted hundreds to Christianity.

· How did Lal Behari and his family find themselves in Nadia district in North Bengal.

· How exactly did Lal Behari lose his eyesight in 1912? One of the fables, which I accepted for a long time and even, wrongfully, passed onto my oldest son, was that his eyes were damaged by coal dust on a trip to Meerut to see his older brother. Subsequently, in reading various self-published biographies by his family, I see that it was through “illness.”

Lal Behari always wore a dhoti and a long coat and he didn’t leave behind anything written in his own hand or a document that reflected his thinking. Years ago, I used to have have pamphlets printed in hot-type of the school’s curriculum but catastrophically I misplaced them.

What Lal Behari did in his 75 years on this earth that makes him such a force in my life is:

He gave tangible hope to thousands who’d lost their sight, a way to study and learn and move along. This at a time when such ideas were almost nonexistent around the world.

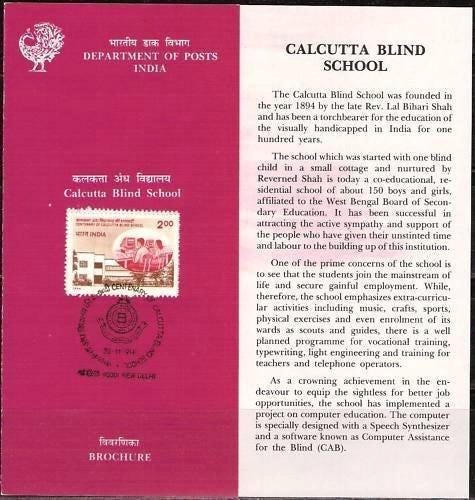

(Postage stamp issued by the Government of India for the centenary of the school. Courtesy of the author. All Rights Reserved)

His school, still functioning and managed by the resources of the current state government, graduated (matriculated) the first visually impaired man to the university in India. Nagendranath Sengupta in 1919.

Savitri Roychowdhury was first woman to matriculate in India in 1938 ( page 29 in the link)

Sadhan Chandra Gupta, the first visually impaired parliamentarian in 1953

I’m going to do two more parts to this post. The second one will focus on Lal Behari’s personal history and I hope to write that in the relief of India’s history during the late 18th and early 19th century and the enormous interactions with colonialists.

The third part will be my own memories and musings of being proud, yet burdened, by the enormity of such selfless work and social contributions. My main intention is to “clean up” the history and not leave such a garbled past for my grandchildren.

____________________________________

Direct purchases available for $17 ($12 plus shipping)

Venmo: @amit-shah-1950 // check to: 39 Whitman Street, Somerville, MA 02144

Also on Kindle at Amazon and paperback at Porter Square Books, Cambridge, MA