Cartographies of Loving

“ There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.” ~ Maya Angelou

“ Be sure to take your shoes off once you’re settled in your seat. It’s a long flight.”

He and I are standing at the edge of the tarmac looking at winking lights of the lone jetliner against the night sky a distance from us. Around us passengers going on board that plane are hopping on to the trolley that’ll ferry them across the few hundred yards. This is as far as he’s allowed to accompany me. I quickly hug him and he kisses my forehead, whispering my nickname. I duck out of the embrace and try, I hope nonchalantly, to dip down to the ground and let my fingers of my right hand touch the warm ground. It’s March and the heat of the day in Calcutta is still trapped in the dirt at my feet. It’s 1971. I have a passport. I have a visa. I have eight dollars in US currency in my pocket and plane tickets that will take me on the most circuitous route I could find on the airlines’ routes ---Calcutta, Bombay, Moscow, Frankfurt, London ( two-night layover at the airlines’ cost: there weren’t very many full-fare paying international passengers in those days, so the perks were piled on) and finally New York.

Fifty years ago, almost to the day, what I was fleeing was more than the tangible fear of physical harm. I was rushing toward hope, some glimmer of a dawn after the night. This was, after all, the first time in my then brief life that I was facing the ruination of hopes. Till then, I had been a lucky and privileged young man, setting my goals and achieving them, like a masterly nine-pin bowler, knocking the pins of my ambitions with little effort.

Let’s step back a few years. Twenty years after India independence, 1967, were lives better now than under the colonizers? The jury was still out. However, by and large corruption, inequality, nepotism, lack of opportunity and the bleakness of the future for the vast majority had simply grown. The landless suffered like medieval serfs. Without social media then, we can only guess at the state of caste hatreds, religious bigotry, the corruption and caste strangleholds of village councils, and the stink of daily oppression for thousands upon thousands.

My college mates and I were possibly the top 1-2% of that society. We were educated, never wondered about hunger, the future was rolling out in front of us, unfurling without a crease and we laughed often.

As a child, when I sat in the back seat of our car as it wound its way on Calcutta roads, I tried not to look at the children, my age and younger, who lived on the sidewalks. But then again, my child’s conscience had an extraordinary balm—-my family ran an educational institution where 99% of the students were poor and blind. This institution was founded and run without government aid for generations. So perhaps I could get a pass? As I finished my first year in college, I couldn’t find a good answer to how I would contribute to making my country better. There didn’t seem to be many options—-civil service, corporate companies, a small and influential journalism sector for English-language publications and academia.

Then Naxalbari, a village in the foothills of the Himalayas, the terai region, belched its tongues of fire in the summer of 1967, and by the summer of 1969, the group that pushed for the first wide-scale revolution for land reform in post-Independence India was banned and its followers and sympathizers went UG (underground), disappearing into the vast maw of the rural and urban working class, or so was the plan.

At its most elemental level, the hundreds of thousands who joined this upsurge in the late sixties were people who wanted to do something toward justice, equity, and human dignity. Many middle-class students poured out of the universities, especially in the eastern section of the country, and went to the rural hinterland in an effort to “do propaganda”, work with the landless to secure better returns for their crops. It was complicated. Indian society is highly classified in every way and the gulf between the rural landless and the city-bred was a galactic mesa of a difference. I, for one, wore glasses, and my spectacles were an instant signal that I was from the city. Hygiene was terrible. You defecated in the fields and carried a tumbler of water to wash up. Once I tried to cajole a schoolboy to part with a page from his notebook to use as toilet paper. He pleaded that the pages were numbered and the teacher would punish him if a page was missing. As with all conflicts, hindsight is always 20-20 and perfect. In hindsight, the work that was required to mobilize the sharecroppers into a viable political force and the city-born a trusted member of that society was cast aside in favor of vigilante-like groups that attacked large landlords and their private armies. The political leadership called for killings. The bloodshed turned the earth’s color and the response of the state, both in the hinterland and in the cities, was titanic. The brutality was spell-binding. None were immune. People like me who’d never held a weapon of any kind bar an air-rifle at age twelve, tried to intellectualize and rationalize the blood-letting and childishly hoping it wouldn’t reach us. (Couldn’t revolutionaries do other things besides kill? Who was asking? Who would answer?) But the catastrophe was more than a misadventure. Our failure was a tragedy. Whispered for generations later. Still.

In the anvil of a pivotal moment in history, my role was decisively quixotic. A few day trips into the villages, a few overnight stays with small farmers who treated me like a visiting dignitary, perplexed by my aims. With special branches of the constabulary keeping close, almost perfect, surveillance of us, the last thing I needed was to become entangled in an intra-group squabble. And that’s exactly what happened. Two groups, all of whom I knew, squared away on local tactics and leadership and instead of fighting for justice and equality, we fought each other in a vicious and clumsy way, in full view of the security forces. One group was methodical in its viciousness. They were the believers. And like all believers, they left their humanity by the roadside to rot in the tropical sun. I was scared to be assaulted, tortured, made an example of. I wanted to flee. And this is where I interject how class and privilege works the world over. People like me, who had the choice, would most likely flee under pressure, according to the intelligence officers. In 1970, Calcutta (now Kolkata) had the following message throughout the city on billboards. “If you are a student or any young person led astray or living under pressure and wish to return to the path of decency and discipline, please feel free to ring up 44–1931, and you will get friendly counsel and personal attention.” (From New York Times, Nov. 26, 1970.) So, they simply waited for me to do that. To leave the country. And that is what I did that March night . . . leave. Flee. Bolt. Run away.

It was a coward’s choice. I had the privilege to exercise choice. The next few decades didn’t put to rest what I knew to be cowardice. All the success and accolades from work weren’t enough to dampen what I felt was a lifelong failure. Someone asked me recently whether staying on and getting brutalized by a group of ideologues in India in the winter of 1970-71 would’ve made a difference. The simple answer, minus my ego is “No.”

What can I do in the face of injustice? I mentor, basically chat, with young people from the poorest urban areas in India each week through an organization that gives them a one-year scholarship to learn English, develop some workplace skills along with a few life skills, skills like overcoming adversity and learning to ask questions. We laugh and talk. In the India I left, they weren’t even allowed to dream and for me to talk with them on a somewhat equal footing was a monumental political act. It’s life-affirming today. I am kind. To my family. To my friends. I leave the past behind.

The person who got me to that edge of the tarmac with a passport, clothes, a plan for the possible future was Baba. To him I owe. He never heard it from me out loud.

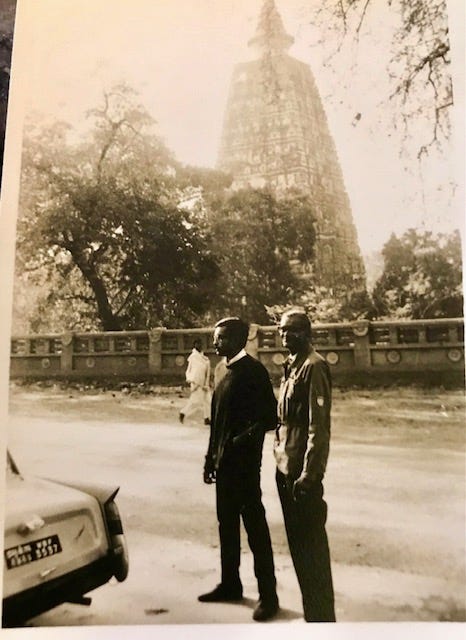

The night I left Delhi---it was a December night. I boarded a third-class Delhi-Howrah train with only what I was wearing and a cloth jhola with toiletries and a change of clothes. All else, including my motorcycle, was in a windowless garage (yes, you read that correctly, a garage) with rolldown metal shutters as the door, close to the north campus of Delhi University. To use the toilet, we had to request the landlord to let us into his first floor next door. Needless to say, I spent only a few nights there in the six months that I rented. I shared this space with Mezda, the middle brother. He was the older brother of my best friend. A few months after I had left town, Mezda, whose name is Pradip, loaded all my belongings including my motorcycle onto a train and escorted it to a train stop at Bodh Gaya about 60 miles from where I was staying. Baba and I with Robi (a friend of my dad’s) met Mezda there. I drove the motorcycle while Mezda sat behind me. I owe him too. Fortunately for me, Mezda and I see each other every few years. I’ve seen his daughter being born and grow up to be a professor in the same town I live in. His wife is like my sister, only closer. His brother, my friend, has died. Mezda and I never talk about that time in early 1971. He didn’t then and doesn’t now think he did something selfless. Something heroic.

Baba and Mezda ---did something out of unalloyed love; not ideology.

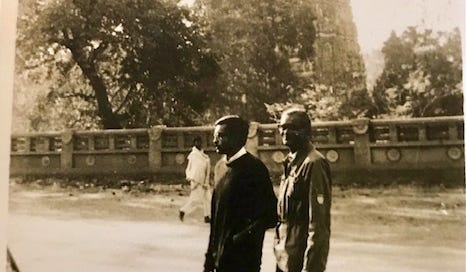

The author on left with Robi, his father’s friend, at Mahabodhi Temple, Bodh Gaya (where the Buddha is said to have attained Enlightenment). February 1971.

Kanchenjunga, the third-highest Himalayan peak at 28,000 + plus feet is glistening gold against the clearest blue sky over the paddy fields, green and manicured, wet with morning dew to our right as Mezda, Chicku, his wife, our friend, Bapi, and I hurtle toward a national forest in the foothills of the Himalayas, an area called Jalpaiguri. My heart is full. This is possible because of . . . inspite of . . .the events of fifty years ago when ideology danced its wretched dance in a claustrophobic night.

A lovely reminiscence. There are diamonds to be found even in the trenches of a lived life. (If you haven't read Jhumpa Lahiri's 'The Lowland', you might find intersections.)

Love this. So amazing to have this glimpse of your early life and its echoes and repercussions now. Also, for me, it's wonderful to have this lens into India, at whatever time. And such beautiful, evocative writing.